Posts Tagged ‘Music: British’

The Robertsbridge Codex (c1325)

The Robertsbridge Codex is a rare little thing. It’s only a few pages in an otherwise obscure manuscript, but it’s noteworthy because it’s the first known collection of music meant specifically for keyboard instruments.

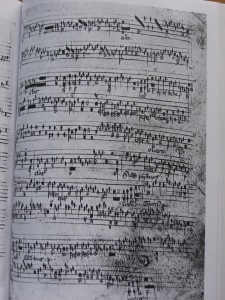

Here’s a page from the Codex. This is a photograph of a page in Carl Parrish’s book, so you might want to look online to get an image with better resolution.

The treasure currently resides in the British Library, in London and the tale of how such an important piece of music came to be in this obscure little place is a good one.

Robertsbridge is a village in East Sussex, England, about 10 miles north of Hastings (made famous in the Battle of Hastings in 1066). The Rother River passes through it. The town is thought to have developed around a 12th century Cistercian abbey, named by Richard I (1157-1199) in 1198 for his steward, one Robert de St. Martin (dates unavailable). It was settled by monks from the mother abbey in Boxley, in Kent, about an hour’s drive north, and was probably built roughly on the site of a war memorial and a spring known as St. Catherine’s well. The monks at Robertsbridge were known as the “white monks” because they wore tunics of undyed wool.

The site was probably originally a small chapel, but it received many gifts and endowments from such families as the Bodiams (who later had a castle nearby) and the Etchinghams (nearby landowners since before the Norman Conquest). As a result, they were able to build a new abbey about a mile east of the original site in about 1210.

The Robertsbridge abbot was sent, along with the abbot from nearby Boxley, to search for King Richard I (1157-1199), who was being held hostage in Bavaria after his return from the Crusades in 1192, and when they found him, they went back to England to raise his ransom. Later, these same two abbots were sent as agents for the Archbishop of Canterbury to see the pope about a quarrel with the monks at Canterbury. In 1212, 1221, and 1225, the abbot of Robertsbridge was again sent as the king’s emissary to Europe (first John then and Henry III twice), and the Henry III also paid the abbey a visit in 1225. The abbey had faded in fame by the 1400s and escaped the first suppression of the monasteries.

It survived until 1538, when it was dissolved under Henry VIII (1491-1597). It was surrendered by the abbot and eight monks—everyone else had long gone. After the dissolution, the abbey buildings were acquired by Sir William Sidney of Penshurst (1482?-1554), and it stayed in that family until 1720. The remains of the abbey survived for most of the 18th century but were then destroyed. All that remains today is the former abbot’s house, now a private residence.

The town flourished without the abbey, with some fine castles and good schools and such. Today, it’s the home of Heather Mills (b.1968), former wife of Beatle Sir Paul McCartney.

Robertsbridge came to fame when the eponymous codex was discovered among other records at Penshurst Place in Tonbridge, Kent (about half an hour’s drive south of London) in the mid-19th century. It was found in a bundle with an old register from the Robertsbridge Abbey. Originally, it was thought to be from as early as 1325, but later scholars determined that 1360 was more likely.

It’s an important document because it’s the earliest known collection of music written specifically for keyboards. It’s also the earliest preserved example of German organ tablature. It’s called “German” because it appears later only in Germany, slightly more developed, where it’s also known as the Ludolf Wilkin tablature, from 1432. This tablature was adopted exclusively for writing down organ music and was used until Samuel Scheidt’s (1587-1654) Tablatura Nova and Johann Ulrich Steigleder’s (1593-1635) Ricercar Tablaturen, replaced it in 1624. After this date, particularly in Northern Germany, many important sources of keyboard music are written in this notation.

It’s a little off topic, but Old German tablature, from the early 15th century to mid-16th century, used letters to identify the notes to be played, rather than neumes or mensural notation on the staff, in all the voices except the highest, which was in neumes that we would recognize as notation today. These highest parts were usually red in color and provided decorative musical figuration; it’s also where we get the term that survives until today in the modern word “coloratura.” Cool, eh?

This tablature also included the squared lower-case B, which resembles a lower-case H that represented B-natural (which nomenclature survived well past Johann Sebastian Bach’s time, where he called things H-moll for B-minor, as in the B Minor Mass) and an S for “sine,” which is Latin for “without,” and meant a rest, or silence.

Another cool thing is that the keyboard selections offered required all twelve keys of the modern octave. It’s the first evidence of this—things were modal and only contained eight notes to an octave before. (You can learn more about modes here: Musical Modes, Part 1: Church Modes.)

The Codex contains other things than music, although I didn’t find a source that said what exactly those other things are. There are only two musical sections, containing six pieces. Three are estampies, which is an Italian dance from the trecento, and had scholars convinced that the music came from Italy originally. Three songs are arrangements of motets, two of which are from the Roman de Fauvel. You can learn more about that in my post, Composer Biography: Philippe de Vitry (1291-1361). The Codex contains instrumental transcriptions of two of Vitry’s Fauvel motets (Firmissime/Adesto and Tribum, quem non abhorriuit), and another motet from Roman de Fauvel with organ accompaniment. There are also three Italian-style dances (estampies).

Now then. On to the music itself.

The Codex contains the end of a purely instrumental piece in the estampie form. There are two complete pieces in this form, the second of which is marked “Retroue.” There’s also an incomplete transcription of the hymn Flos vernalis. These may have been meant to be played on an organ, and a little later, Edward III (1312-1377) presented his captive, John II of France (1319-1364) with an eschiquier (an instrument that was the predecessor to the harpsichord) and a copy of the piece.

The Robertsbridge transcriber went a little heavy on ficta (accidentals, more often sharps than flats), to the point of inserting naturals to return the note to its original state rather than assuming the natural as the default. He also transposed one piece from the Fauvel motet up a step, forcing a single sharp into the key signature of the right hand. (The left hand had its own key signature and stayed as it was.) He also occasionally added notes where he thought the harmony was too thin.

It’s possible that the motets were included in the Robertsbridge Codex for political reasons as allegories for political events of the period, such as the public hanging of Philip the Fair’s (France, 1268-1314) unpopular chancellor Enguerrand de Marigny (1250-1315), or about some enemy of Robert of Anjou, King of Naples (1277-1343), or perhaps a celebration of the new Pope Clement IV (1190-1268).

All of the music is unattributed (late scholars have identified de Vitry as one source), and all is written in tablature. The estampies are written for two voices, often in parallel fifths and using the hocket technique (where one voice has artful rests that are filled in by another voice, like an exchange of hiccups).

It’s important to note that at this time (the 14th century), organ keys became narrower so that more could fit onto a keyboard table, and also accommodating a wider range of pitches (such as 12 notes to an octave) and sustained chords. This made it possible for a rhythmically fluid and complex decorative voice to unfold beyond the earlier isorhythmic pieces. Robertsbridge features an isorhythmic motet with a patterned scaffolding in the left hand as a foundation for a dramatic instrumental display played by the right hand. This became a pattern that we’re still using today.

The Rupertsbridge Codex marks the beginning of our modern sense of a slower or chordal left hand with a busy and ornamental right hand. Despite its quiet lack of fame, it’s really a very important document.

Sources:

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1994.

“The History of Western Music,” by J. Peter Burkholder, Donald Jay Grout, and Claude V. Palisca. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2010.

“The Concise Oxford History of Music,” by Gerald Abraham. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1979.

“The Notation of Polyphonic Music, 900-1600,” by Willi Apel. The Mediaeval Academy of America, Cambridge, 1961.

“The Notation of Medieval Music,” by Carl Parrish. Pendragon Press, New York, 1978.

“Early Medieval Music up to 1300,” edited by Dom Anselm Hughes. Oxford University Press, London, 1954.

“Music in Medieval Manuscripts,” by Nicolas Bell. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2001.

“Companion to Medieval & Renaissance Music,” edited by Tess Knighton and David Fallows. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1997.

“Music in the Medieval West; Western Music in Context,” by Margot Fassler. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2014.

“Music in the Renaissance,” by Gustave Reese. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1959.

Composer Biography: Peter Philips (c1560-1628)

(Also Peter Philipps, Peter Phillips, Pierre Philippe, Pietro Philippi, and Petrus Philippus)

Peter Philips, although he spent most of his life in Europe, was one of the biggest names in English music. He was an organist and a Catholic priest, and his work could be heard from Rome to London to Brussels, and beyond.

He was one of the great keyboard virtuosos of his time, and transcribed or arranged several Italian motets and madrigals by Orlando Lassus (1532-1594), Giovanni Pierluigi Palestrina (c1525-1594), and Giulio Caccini (1551-1618). Some of his keyboard works are found in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, and he wrote many sacred choral works as well.

He was possibly born in London, although there are stories that he came from Devonshire. Nothing is known about his family, but they weren’t particularly wealthy. They were particularly Catholic, and that would color Philips’ life.

When first we hear of him, Philips was a choirboy at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London in 1574, serving under Sebastian Westcot (d.1582), who had also trained William Byrd 20 years earlier. Philips must have been close to Westcot, as he stayed at the older man’s house until Westcot died. He was named as a beneficiary in Westcot’s will.

He was possibly one of William Byrd’s students, along with Thomas Morley (c1557-1602) and Thomas Tomkins (1572-1656), Thomas Weelkes (1576-1623), and John Bull (c1562-1628).

That same year (1582), Philips had to emigrate because he was Catholic. He landed in Flanders, Europe’s third biggest musical center (after Rome and Paris). He stayed for a bit, and then headed out for Rome, the center of both Catholicism and music. There, he was in the service of Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589), with whom he stayed for three years. At the same time, he was organist at the English Jesuit College in Rome from 1582-1585.

In 1585, he met Thomas, third Baron Paget (c1544-1590) and became a court musician for him instead. The two left Rome, traveling over the next few years to Genoa, Madrid, Paris, Brussels, and finally Antwerp, where Philips settled in 1590, when Paget died.

After he settled, Philips married and gained a precarious living by teaching the virginal to children. In 1593, he went to Amsterdam to see and hear Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621), whose reputation was already huge. On his way home from that exciting visit, he was denounced by another Englishman for conspiring to assassinate Queen Elizabeth. He was temporarily jailed at The Hague, where he composed both the pavan and galliard Doloroso that are in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (more on that later). He was soon freed for lack of proof.

When he returned to Brussels, Philips was employed as organist in the chapel of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, who’d been appointed governor of the Low Countries in 1595, two years earlier.

After Philips’ wife and child died, he was ordained as a priest in 1601 or so, and became canon at Soignies in 1610. He also became a canon at Beithune in 1622 or 1623. These were meager livings, but at least he knew that he had a regular income.

In his new position at Albert VII’s court, he met the best musicians of the time, including Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643), who visited the Low Countries between 1601 and 1608, and John Bull (c1562-1628), who had also fled England but for different reasons: he’d been charged with adultery.

Philips’ was close to fellow organist Peter Cornet (c1575-1633), who worked for the Archduchess Isabella, wife of Philips’ employer.

He wasn’t very well known in England during his lifetime, but he was famous in northern Europe as a fine organist and versatile composer. He’s considered second only to William Byrd as the most published English compose of his day. His music for keyboards and instrumental ensembles are in the traditional English style, and his Italian madrigals including some for double choir (in three books, collected from 1596-1603) and his motets (five books, from 1612-1628), show continental style and influence, especially Roman.

Philips was important in bringing the English musical style to the Continent and he was probably the most famous English composer of his day in Northern Europe.

Philips composed Masses, hundreds of motets (sacred madrigals), other sacred works, madrigals (secular motets), pieces for viols, and27 pieces for virginal. His religious music was entirely meant for Catholic use, unlike that of Catholics in England, who either composed for Anglican services or secretly composed for Catholic uses (see composer biographies on William Byrd and Thomas Tallis).

He produced three books of madrigals, two books of choral motets, three books of concertato motets (instrumental) of one-to-three voices with continuo accompaniment, a book of Litanies (a form of musical prayer in both Jewish and Christian traditions), and a book of bicinia (pedagogical music in two parts) with French texts.

His keyboard music was preserved in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

His madrigals (secular vocal music) belong to a conservative Italian tradition, probably thanks to his training in Rome. He uses colorful textures and sonorities, although his instrumental motets show him keeping up with the latest trends and styles. His keyboard music includes transcriptions and reworking of well-known Italian madrigals, one of which is Giulo Romola Caccini’s (15510-1618) monody (chant) Amarilli.

His first set of Cantiones sacre (in five voices) was printed by Pierre Phalese the Younger (dates unknown) in 1612, followed in 1613 by a second set for double chorus. Later publications contained sacred works for two and three voices, as well as some for solo with basso continuo and a set of Litanies (musical prayer, petitions mostly) to the Blessed Virgin in four to nine voices, which appeared between 1613-1633 (there is one source that says that Philips died in 1633 rather than 1628, but it’s more likely that the pieces were published posthumously).

He put together one book, called Les Rossignols spirituels, that was an arrangement of popular melodies adapted to sacred texts, in 1616.

He used a lot of different techniques, like the imitation (see Composer Biography: Johannes Ciconia), in a variety of ways, exhibiting considerable freedom, and modifying and combining different forms with imagination and skill. Like Flemish composer Orlando Lassus (1532-1594), he often imitated a rhythmic pattern or a melodic contour throughout a piece.

Philips’ Alma Redemptoris Mater, a richly polyphonic work, opens with a motif that’s imitated by three voices and then inverted by the other two voices. After each voice has sung the motif once, that voice presents the motif in a new form, perhaps borrowing a motif from one of the other voices.

His Elegi abjectus, esse uses real imitation in the opening among three voices. A fourth voice offers a more tonal answer, and the alto sings freely, disregarding the motif altogether. The motif is presented without interruption by the tenor; the other three voices break the motif with silence.

Another piece, Ascendit Deus, is simpler, with broken major triads in some sections, bright melismas in others, and a rousing chordal final “alleluia” section. The setting for the words “et Dominus” uses imitation in all its forms: a real answer, a tonal answer, imitation by inversion, and imitation of rhythmic patterns.

Philips draws on chant for Pater Noster, which uses the old cantus firmus style (with the chant sung slowly in the tenor line while the other parts trip merrily around it) and for his Ave Maria, Regina coeli, and Salve Regina, which use the paraphrase technique. He particularly shows his expertise with madrigals in the Salve Regina.

His earliest surviving piece is a pavan dated 1580, that’s in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. It was the subject of many variations by Dutchman Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621), and Thomas Morley (c1557-1602), and John Dowland (1563-1626), both British.

The compiler of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, Francis Tregian the Younger, also a Catholic, knew Philips from the court of Brussels in 1603. Tregian may have been responsible for importing Philips’ works to England.

Flemish composer Andreas Pevernage (c1542-1591) collected madrigals and dedicated one of his collections to Philips, who had five pieces in the book. The madrigal had taken such firm root in England by then that it was second only to Italy in output.

Philips died in 1628, probably in Brussels, and was buried there.

Sources:

“A Dictionary of Early Music; From the Troubadours to Monteverdi,” by Jerome and Elizabeth Roche. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981.

“Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music,” by Don Michael Randel. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978.

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1994.

“The New Grove High Renaissance Masters,” by Jeremy Noble, Gustave Reese, Lewis Lockwood, James Harr, Joseph Kerman, Robert Stevenson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1984.

“Music in the Renaissance,” by Gustave Reese. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1959.

Composer Biography: Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625)

Did you ever hear that expression: he died of apoplexy? Well, you’re about to hear the story of someone who did exactly that. Orlando Gibbons was an English composer, virginalist, and organist of the late Tudor and early Jacobean periods. He was a leading composer during his lifetime and remains a favorite among Renaissance musicians around the world.

In fact, in the 20th century, famed Canadian pianist Glenn Gould (1932-1982) named Gibbons as his favorite composer, comparing him to Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) and Anton Webern (1883-1945). And to this day, Gibbons’ memorial service is commemorated every June at King’s College Chapel at Cambridge.

Gibbons was born in Oxford, England, the youngest of William Gibbons’ (dates unknown) four sons. William was a town piper for Oxford and later for Cambridge, but it was his children who showed a real gift for music. Orlando’s eldest brother Edward (1568-1650) became the master of the choristers at Cambridge, and his next brother, Ellis (1573-1603), was also a composer of some repute. Ellis’ works were published along with Thomas Morley’s (c1557-1602, biography coming soon) in a collection of madrigals that were published in 1601. This was a great honor.

The family moved from Oxford to Cambridge between Orlando’s birth and his christening. At Cambridge, he became a chorister at King’s College in 1596 at 13 years old and stayed in the choir for two years. He attended the college between 1599 until 1606, earning a Bachelor of Music. He earned a Doctorate of Music at Oxford in 1622.

King James I appointed Gibbons to Chapel Royal (you can read more about that organization in my blog post On Henry VIII’s MP3 Player), where he served as organist from 1615 until his death. In 1623, he was promoted to senior organist at Chapel Royal with Thomas Tomkins (1572-1576), another famous musician, as his junior organist. He was also a keyboard player in the privy chamber of the court of Prince Charles (later King Charles I) and an organist at Westminster Abbey.

Gibbons began composing at age 16, and by age 29, he had published keyboard music in Parthenia (c1612) the most prestigious publication of keyboard music of the time. His work was intended for virginals, but at the time, the word meant any plucked keyboard instrument, such as a harpsichord, clavichord, chamber organ, muselaar (a virginal with the keyboard on the right end of the box), or the virginal (there will be a blog post on these soon) as we know it today. (The piano wasn’t invented until the very early 18th century.)

Gibbons earned the reputation of being one of the most important English composers of sacred music in the early 17th century, writing several Anglican services that were popular in their day (and still are), and over 30 anthems, some imposing and dramatic (such as O clap your hands), others colorful and most expressive (such as See, the word is incarnate, and This is the record of John, which, along with O clap your hands, is probably his most famous and often performed work). His instrumental music includes over 30 elaborate contrapuntal viol fantasias and over 40 masterly keyboard pieces. His madrigals (published in 1612) are generally serious in tone (such as The Silver Swan, which is probably MY favorite piece of his, and most certainly the first piece of his I performed alone on the soprano line). He was easily one of the most versatile composers of his time.

Six of his pieces are in the first printed collection of English music, Parthenia, which was dedicated to Frederick, King of Germany and Lady Elizabeth, the daughter of King James I. Gibbons was the youngest of the three contributors that included John Bull (c1562-1628) and William Byrd (c1540-1623), two of the most famous keyboard composers of their time. Gibbons’ surviving keyboard output is about 45 pieces with his polyphonic fantasia and dance forms providing the most pieces.

His writing shows full mastery of three- and four-part counterpoint (where independent melodic voices—polyphony– intersect rhythmically). Most of the fantasias are complex, multi-sectional pieces, treating multiple subjects imitatively. Gibbons’ approach to melody shows that he can almost infinitely develop simple musical ideas. Mozart was like that too, rather famously writing elaborate variations for the song we know as Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.

Gibbons’ choral music is distinguished by his skill with counterpoint combined with a wonderful gift for melody. He wrote sacred music, including full and verse anthems, services, and psalms, plus secular madrigals, fantasies, and works for viols, and of course, his compositions for virginals.

He wrote over 30 anthems, 25 of which have highly developed polyphony for viols in the solo sections, and during which the vocal soloists repeat the text from the choral sections. He also wrote two Anglican services, some psalms, a Te Deum, and hymn tunes. He produced two major settings of Evensong: the Short Service (including Nunc dimitis) and the Second Service, which was lengthy and combined verse and full sections.

He wrote 14 madrigals (secular vocal music) and consort songs (polyphonic songs intended for “families” of instruments; for more on this, see my post on recorders). He also wrote over 30 fantasias (a freely structured piece that leaves lots of room for improvisation by soloists) for viol, plus pavans (a slow processional dance), galliards (a choreographed and fairly athletic dance), In Nomines (see my blog post on John Taverner for more about this genre), and allemandes (an instrumental-only dance that was a movement in a suite of songs).

His death was sudden and violent. It was initially supposed that Gibbons died of the plague, which was rampant in England in 1623. The two physicians present at his death were ordered to perform an autopsy and make a report, and there’s a copy of it in The National Archives. It says that he went into convulsions, his eyes bulging. He lost speech, sight, and hearing (although this seems like a presumption, just because he wasn’t able to respond). He then grew apoplectic and became paralyzed. Gibbons was at first lethargic or “profoundly asleep,” and they couldn’t wake him. Then he died. There were no marks from the plague on his corpse, which these doctors had examined by trustworthy women (they weren’t at all confident that it wasn’t the plague, and didn’t want to risk exposure themselves). When they opened his skull, water and blood gushed out, and they found blackness in the outside area of the brain. Yuck

His death was shocking to his peers, and they were just as shocked at the haste with which he was buried. It was also surprising that he was buried at Canterbury (where he died) rather than being returned to London. There’s a monument to him there at Canterbury Cathedral.

Gibbons’ wife Elizabeth died a little over a year later, in her mid-30s, leaving Orlando’s eldest brother Edward to care for their orphaned children. Of these, only the second son, the first of Orlando’s surviving children, Christopher Gibbons (1615-1676), became a musician.

Sources:

“The New Grove High Renaissance Masters,” by Jeremy Noble, Gustave Reese, Lewis Lockwood, Jessie Ann Owens, James Haar, Joseph Kerman, Robert Stevenson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1984.

“Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music,” by Don Michael Randel. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978.

“The Concise Oxford History of Music,” by Gerald Abraham. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1985.

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1994.

“The Pelican History of Music, Book 2: Renaissance and Baroque,” edited by Alec Robertson and Denis Stevens. Penguin Books, Harmondshire, 1974.

Composer Biography: William Byrd (1543-1623)

This post also appears in a slightly less musician-centric form as a guest post on http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/ on October 30, 2103.

You know how some people relate best to their parents’ generation? William Byrd was like that, being very much an Elizabethan figure (she reigned from 1558-1603), despite composing well into James I’s reign (1603-1625). His music and affinities belonged more to Edmund Spenser’s (c1552-1599) time than to that of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) or Francis Bacon (1561-1626), even though they were contemporaries. Byrd was firmly part of the group that defined Elizabethan culture, and it was his musical innovations that shaped what would become known as the English sound.

Byrd’s motets, the English version of the Italian madrigal, are the epitome of High Renaissance style. He also took the disheveled condition of English song in the1560s and pulled it together to produce a rich and extensive repertoire of songs for consorts, a form that Byrd took seriously and that had no true imitators. (For more on consorts, see my posts on the vielle, the recorder, and the cornetto.) He influenced lute songs with his consort pieces, and these evolved into what would become a distinctively English anthem form, Byrd’s most lasting legacy in English music.

His works for the virginal (a harpsichord-like keyboard instrument) transformed it from a parlor toy into an instrument of power and beauty. Byrd changed the direction of keyboard music, making it possible for later lights to shine, such as Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) and Frederic Chopin (1810-1949)—especially after the invention of the piano in 1770 or so.

Byrd’s direct impact on English composition can be compared to that of Shakespeare’s influence on the theater. Thomas Morley (c1557-1602) and Thomas Tomkins (1572-1656) were his pupils, and possibly Peter Philips (c1560-1628), Thomas Weelkes (1576-1623), and John Bull (c1562-1628). These, if you hadn’t guessed, are the royalty of English music during the Renaissance.

Byrd’s date of birth is approximated based on his 1622 will, when he wrote that he was in his 80th year. He probably grew up in Lincoln because his first professional appointment was there, but there are no birth records to verify it. Byrd was a common surname in Lincoln around that time.

Several musicians named Byrd appear in mid-century London records, and Thomas Byrd (dates not available), a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal in the 1540s and 1550s, may well have been his father (and if true, his mother‘s name was Margery). There are some compositions ascribed to Thomas and some just to “birdie;” Thomas wasn’t really known for his compositions, though, not the way William would be.

A Fettered Brilliance

He must have spent some of his formative years in London because he was Thomas Tallis’ pupil in 1575, or so said another Tallis student, courtier and amateur composer Sir Ferdinando Richardson (c1558-1618). Byrd grew up during Mary Tudor’s short reign, perhaps even in her Chapel Royal, and his early works were influenced by the big composers that had come before and whose music was still performed at court, including Robert Fayrfax (1461-1521) and John Taverner (1495-1545).

It’s probable that some of Byrd’s surviving compositions are from his teens. Three of the motets attributed to him are for the Sarum liturgy (an English interpretation of the Roman rite started in the 11th century, reinterpreted for the Anglican church in the 16th century, and ended during Mary Tudor’s reign), and indicate that he was composing before the death of Queen Mary, when he was 16 years old.

In 1558, Elizabeth became Queen of England, and the attitude toward Catholics changed. Although Elizabeth was fond of her two resident Catholic composers in the Chapel Royal, Byrd and Thomas Tallis, they weren’t allowed to openly practice their religion, and she wanted music composed that suited the new Church of England’s very British sensibilities.

In 1563, Byrd succeeded Robert Parsons (c1535-1572) as organist of Lincolnshire Cathedral (note that Parsons was not old enough to retire and he died by drowning rather than illness—there’s probably a good story there). Byrd was given a larger salary than usual as Master of the Choristers at Lincolnshire Cathedral and he lived for free at the rectory at Hainton, in Lincolnshire.

During his tenure at Lincoln, he experimented with a lot of different styles, forms, and genres. His idols were ThomasTallis (c1505-1585), Christopher Tye (c1505-c1572), John Redford (d1547), Robert White (c1538-1674), Robert Parsons (c1535-1572), William Hunnis (d1597), and later, the emigrant composers Philip van Wilder (Netherlander, 1500-1554) and Alfonso Ferrabosco the Elder (Italian, 1543-1588). All served as models, and some suggested ideas, techniques, textures, or ground plans (somewhat like today’s bass chord progressions), and some provided material that Byrd used as starting points. In 1583 and 1584, Byrd had a musical exchange of motets with Flemish composer Philippe de Monte (1521-1603), where one supplied lyrics or melody, and the other responded with the rest.

Byrd married Juliana Birley (d. c1586) in 1568 at St. Margaret’s-in-the-Close in Lincoln. They had seven children: Christopher (1569-1615), Elizabeth (c1572- ?), Rachel (c1573- ?), Mary and Catherine (with no known dates), and twins Thomas and Edward (c1576-after 1651). Thomas was named after his godfather Thomas Tallis (or possibly William’s father) and was the only one of Byrd’s children to become a musician. After Juliana’s death, Byrd remarried a woman named Ellen (no known dates or surname). It’s possible that Mary and Catherine were products of the second marriage, as their dates are not recorded.

While at Lincoln, Byrd wrote most of his English liturgical music, although relatively little polyphony was required there. It looks, in fact, like he was trying to master all the genres, perhaps to get a better job in London. It worked.

Byrd was sworn in as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal in 1570, but he didn’t move to London until 1572, when the accidental drowning death of Robert Parsons left an opening in the Chapel’s residencies. In 1573, after he’d left for London and his successor had been appointed (at a lower salary), the Lincolnshire chapter agreed, under pressure from certain councilors of the Queen, to continue paying Byrd on the condition that he continue sending musical compositions for their use. He received a quarter of his former salary (in addition to his Chapel Royal salary) until 1581.

In London, Byrd’s success was undeniable. For the next two decades, his name appears in relation to all kinds of important and powerful people. Elizabethan lords figure among the dedicatees for his various publications, and some were known to intercede on his behalf occasionally.

Around 1573 or 1574, he rented Battails Hall in Stapleford Abbots in Essex from the Earl of Oxford, the poet. This property—and others—would involve him in a series of vitriolic litigations.

As a member of the Royal Chapel in London, Byrd shared the post of organist with Thomas Tallis. In 1575, Queen Elizabeth I granted the two composers a monopoly to print and market part-music and lined music paper, a trade with a previously limited presence in England. The immediate fruit of this labor was Cantiones Sacres, a collection of more than 60 sacred works, published that same year.

The contents of Cantiones Sacres were performed at Elizabeth I’s Chapel Royal. But otherwise, the publication didn’t do well and the pair published nothing further for 13 years. In 1577, they complained to the queen that their patent wasn’t profitable and petitioned for further benefits. Byrd received the Manor of Longney in Gloucestershire as a result. It would later be the source of more litigation.

Between 1563 and 1578, Alfonso Ferrabosco the Elder (1543-1588), a prolific Italian composer, was in England in Elizabeth’s service, and was probably a spy. He was the son of Domenico Ferrabosco (1513-1574), an early madrigalist and former colleague of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palastrina (c1525-1594) at the Vatican. Alfonso, as a motet composer, had learned the style of Netherlander Orlando de Lassus (c1532-1594), and through him, Byrd came to understand the classical Netherlands imitative polyphony.

Times were tough for Catholics, and noblemen held secret Mass services in their private chapels. Few were prosecuted for this treasonous act, although it’s doubtful that Elizabeth I turned a blind eye. Byrd and Tallis were public figures and they had to put on a show of compliance.

But Byrd was known to be a Roman Catholic recusant and he risked prosecution by writing Masses for undercover use. For English Catholics, 1581 became a year of decision and renewed commitment. In Harlingon, Byrd’s wife was cited for recusancy along with a servant. Byrd himself wasn’t cited until 1585, when lists of suspected recusant gathering places named his own house. The Byrd family was repeatedly accused of being recusants and in 1605, they were accused of being long-time seducers for the Catholic cause.

It was a terrible period for English Catholics, with rumors flying, forced retirement, assassinations, and executions. Byrd’s home at Harlington was searched twice, perhaps because he was there when he should have been in London. Byrd and his family were fined hugely, but there were concessions, probably at the behest of Elizabeth I. After all, he was still composing official pieces for her.

In the middle of all this turmoil, Juliana died in 1586 or so, and Byrd married Ellen.

In 1587, Byrd renewed his efforts at publishing. Both Tallis and Thomas Vautrollier (d.1587), the printer of the Cantiones Sacrae, had recently died, leaving Byrd in sole possession of the patent and free to make more advantageous business arrangements. With the printer Thomas East (c1540-c1608) as his assignee, Byrd presided over the first truly great years of English music printing.

Byrd began collecting a retrospective of his own music between 1588 and 1591, and he turned his attention to publishing purely English collections.

His first real success was the Psalmes, Sonets, and Songs of 1588, the third known book of English songs ever to be published. The pieces were originally written for solo voice and instrumental consort, but had been adapted for five vocal parts. Someone later intabulated the collection for keyboard, although it probably wasn’t Byrd. The collection sold out that first year, and East printed two further editions before 1593. Byrd prepared another book for publication, converting a few pieces to vocal-only and writing a bunch of new pieces to be included, including two carols, and an anthem called Christ rising. This second book was for three, four, five, and six parts, as well as vocal soloist with consort accompaniment.

Italian madrigals were hitting it big in England, but Byrd wasn’t particularly excited by them. His 1589 publication barely touched on them. Ferrabosco, who’d left England in 1578, printed his own offerings to the English music scene in Nicholas Yonge’s (c1560-1619) translated madrigal anthology.

After 1590, Byrd’s attitude toward Latin sacred music underwent a change. Where his early motets had been penitential meditations, prayers, exhortations, and protests on behalf of the Catholic community, he started to work on a grandiose scheme to provide music specifically for Catholic services. The texts were drawn from the liturgy, and the music itself became less monumental, to serve the liturgical purpose of a shorter service. It was a new way to serve the recusant cause.

If the music was truly to serve, Byrd had to publish it. But even with his connections in high places, it was a dangerous undertaking. His most famous Masses were printed between 1593 and 1595, each in its own slim book, with no title pages or publication dates. (More on these later.)

Byrd’s fifth collection wasn’t published in his lifetime. It was called My Ladye Nevells Booke, and was dated 1591. One branch of the Nevell family lived at Uxbridge, near Harlington, but the lady in question hasn’t been identified. At any rate, Byrd preserved the best of his virginal music in this book, both old and new. Among these were the last fantasias that he composed.

In 1593, Byrd moved further from London to a large property in Stondon Massey, Essex, between Chipping Ongar and Ingatestone. Ingatestone and Thorndon were the two seats of his patrons, the Petre family, and he probably joined the local recusant Catholic community over which the Petres presided. He composed some pieces for the clandestine Masses, and he dedicated Book 2 of his Gradualia to Lord Petre. His most famous settings of the Ordinary of the Mass were probably first written for the Petres.

In 1593, Byrd moved his family to Essex, where he spent the rest of his life. When his publishing patent expired in 1598, it went to Thomas Morley (c1557-1602, biography coming soon), and a broader range of music in greater quantity began to be published, which implies that Byrd had censored which works he printed.

Byrd spent increasingly less time in London, and his name doesn’t appear in any of the lists of witnesses and petitioners recorded in the Cheque Book of the Chapel Royal between 1592 and 1623, except in the formal register of the members.

He continued to compose, although new music reigned in London and his style of music was as out of fashion as his religion. He spent most of his time dealing with litigation about the numerous leases he’d acquired by grant or purchase. There were at least six lawsuits, and all of them dragged on; the one regarding Stondon Massey lasted 17 years. Byrd was not always in the right, and when he was the one suing, he was unpleasantly tenacious. Even in his will, he mentions a quarrel with his daughter-in-law Catherine and the “undutiful obstinacy of one whom I am unwilling to name.”

Byrd’s three Latin Masses (more about these later) were published openly in the 1590s, and after publication of the Gradualia (in 1605 and 1607, for use with the Catholic liturgy), possession of either book became a criminal offence. With the Gradualia of 1605, Byrd’s half-hearted effort to conceal his identity was abandoned. The political climate was more favorable in 1605, but things changed with the Gunpowder Plot (a failed Catholic uprising against James I), and at least one person was arrested for merely being in possession of the Gradualia. Byrd’s response was to withdraw the books and store the pages.

Byrd’s Gradualia constitutes a sort of musical profession of faith and most of the texts in the collection refer to doctrines that had been attacked or watered down by the Reformers. The music offers many striking examples of contrapuntal virtuosity, word-painting, and a very original use of chromatic devices.

In the 1570s, Byrd began writing his series of pavans (slow processional dances) and galliards (a spirited dance in three-beat rhythms) for keyboard. These, according to the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (the seminal keyboard resource for the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras), were the first that Byrd wrote, and exist in a second version for five-part consort.

It would be nice to know how many Jacobean households celebrated Mass with Byrd’s Gradualia. Appleton Hall in Norfolk was certainly one. It was the home of Edward Paston, and was best known as the home of the Paston Letters (a collection of letters and papers from between 1422 and 1509). Byrd set some of Paston’s poetry to music in the consort-song style that he developed between 1596 and 1612.

Compositions

Byrd was both a traditionalist and an innovator, converting Continental ideas of counterpoint and imitation into a new native-English tradition, and his expressive range was unusually wide.

Although his works were colored by the times in which he lived, many of his motets, galliards, and pastorals are exuberant and joyous. As a precaution against religious persecution, he took his texts from the Bible and other unassailable sources and he wrote for both Catholic and Anglican churches with equal genius.

His lifetime output—at least what is credited to him—includes 180 motets, three Latin Masses, four Anglican Services, dozens of anthems, secular part-songs, fantasias and other works for viol consort, and variations, fantasias, dances, and other works for keyboards. His vocal music includes psalms, sonnets and songs, and around 50 consort songs that could be sung or played by a consort of instruments.

Byrd’s motets are full of musical audacities. One unique feature is called double imitation, where the “subject” melody is applied to two text fragments, and then both are broken down into sub-themes that are further developed and combined. It’s this double imitation that set Byrd apart from other contemporary composers, such as Thomas Tallis, and even his own earlier works.

During Byrd’s lifetime, there were few opportunities to perform his Latin motets publically because the requirement was that the new Anglican rite be sung in English only. His Latin motets capture the spirit of his religious loyalties and he probably wrote so many of them as a way of comforting the Catholic community that celebrated their faith in secret. He was fond of comparing the Catholic situation in England to that of the Jews in Biblical times; some of his motets lament for Jerusalem at the time of Babylonian captivity, some pray that the congregation might be liberated, and others are on the theme of the coming of God that was foretold in the Old Testament. But it was probably this very limitation that spurred Byrd’s creative juices into inventing the anthem.

The anthem fills the spot in the Anglican church service that had been left vacant by plucking out the Latin motet. Many of its features are similar, such as being intended for trained singers rather than the congregation, having verses and a repeated chorus section with different melodies, and having the option for the verses to be sung by soloists rather than the choir, which is called a verse anthem.

The verse anthem, quite popular by the late-16th century, was first accompanied only by an organ, but then Byrd added a quartet of viols. Byrd doesn’t repeat the text from a solo in a choral section, but that was the usual way of things for other composers of the time.

The secular songs he wrote predate the true madrigal (an Italian form of polyphony that lasted from the late 16th century until the mid 17th), and used intricate, flowing counterpoint derived from an earlier English style like that of Tallis (c1505-1585) and Taverner (1495-1545). His motets show him well free of the “for every syllable a note” restriction set up by Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556) during the Reformation, and reveal his mastery of freely imitative polyphony.

Byrd’s early settings of English poems were strophic songs, where all verses and choruses use the same tune—nowadays, we think of this as “normal,” but it wasn’t always so. Instead he used a single voice and a consort of viols. For the viol consort without a solo voice, he wrote 14 fantasies, grounds, dances, and In Nomines (for more on In Nomines, read my blog post on John Taverner), plus 10 hymns and Miserere settings.

Like many other composers before and after him, Byrd used existing melodies, such as Greensleeves, in bits and pieces, throughout his consort pieces. It was a way of using tunes that would have been familiar to the congregation, and it offers today’s musicologists an insight into secular melodies, which were much less well documented than church music.

Byrd was only 10 years old in 1553 when Mary Tudor took the throne, so it’s unlikely that his Masses were much influenced by the five years of safety that her reign offered to Catholics. Despite the covert nature of his religious affinities, his Masses convey a certain freedom that it was never possible to display publically during his lifetime.

He used Continental-style patterns of imitation, but his occasional elaborate melismas (fancy bits where a single syllable is sung across a lot of notes) were more ornate than anything done by his predecessors. His Great Service uses imitative polyphony with frequent repetition of the text during the doxology (a short praise hymn that is often appended to the end of canticles, psalms, and hymns). This innovation would be widely imitated by later composers.

Many of Byrd’s Catholic contemporaries left England in order to practice their religion without persecution. Byrd didn’t, and the three Masses he’s most famous for (in three, four, and five voices, respectively) were published in the 1590s and soon retracted.

Life as a Catholic was difficult, and his works reflect that. All are fairly short, suitable for clandestine celebrations of Mass. Their contrapuntal style is remarkable for the variety of rhythms displayed during such short works. In this respect, Byrd’s music is more accessible to modern ears than other works from the predominantly Catholic Continent.

He wrote 140 pieces for keyboard, including 11 fantasies, 14 variations, grounds, descriptive pieces, and a bunch of dances including 20 pavans and galliards. Some were published in Parthenia (1612-13), and many appeared in My Lady’s Nevells Book (1585-1590), and the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (1562-1612).

Byrd’s teaching was preserved by Thomas Morley in his Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke from 1597, which contains many remarkable tributes to Byrd. Luckily for posterity, Byrd also anthologized his own works, and his legacy in England is deservedly as great as that of Josquin (c1440-1521) in Europe. He was constantly learning and improving on his own work, and through his anthologies, it’s possible to see how he carefully reworked problems he’d been unable to resolve in his earlier works.

His last printed works were four quiet sacred songs that he published in Sir William Leighton’s Teares or Lamentations of a Sorrowful Soule in 1614.

Byrd died a wealthy man at Stondon Massy on the 4th of July in 1623. He was probably buried in the parish churchyard as specified by his will, but his grave hasn’t been located. The will also states that he had apartments in the London house of the Earl of Worcester, which suggests that he might have been a private musician there. He also had a chamber in the Petres’ house at West Thorndon.

The only known portrait of Byrd was painted 105 years after his death and is therefore unreliable.

Sources:

“The Encyclopedia of Music,” by Max Wade-Matthews and Wendt Thompson. Lorenz Books, Leicestershire, 2012.

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1994.

“A History of Western Music,” by J. Peter Burkholder, Donald Jay Grout, and Claude V. Palisca. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2010.

“The Concise Oxford History of Music,” by Gerald Abraham. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1985.

“Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music,” by Don Michael Randel. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978.

“The Pelican History of Music, Book 2: Renaissance and Baroque,” edited by Alec Robertson and Denis Stevens. Penguin Books, Middlesex, 1973.

“Companion to Medieval & Renaissance Music,” edited by Tess Knighton and David Fallows. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1997.

“The New Grove High Renaissance Masters,” by Jeremy Noble, Gustave Reese, Lewis Lockwood, James Harr, Joseph Kerman, Robert Stevenson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1984.

Composer Biography: Alfonso Ferrabosco the Elder (1543-1588)

Although much of his life was spent as an ordinary court musician, Alfonso Ferrabosco the Elder had moments of notoriety that quietly upset the proverbial British teakettle. He came from a family of musicians and fathered another great family of musicians, and saw the Vatican from the choir loft, France from the home of the Duke of Savoy, and England from Queen Elizabeth I’s court. He also hung out with England’s most famous musicians, including William Byrd, Thomas Morley, and John Dowland.

Ferrabosco was born in Bologna, the son of Domenico Ferabosco (note spelling difference). Domenico (1513-1574) may be the same person who was dismissed from being maestro of the Papal choir at St. Petronio for being married and who later became maestro at a Roman church. That older Ferabosco published a volume of madrigals in 1542 and contributed others to anthologies. HIs song Io mi son giovinetta was especially popular and Giovanni Pieluigi da Palestrina (c1525-1594), probably the most famous musician and composer of the era, based a Mass on it.

Other composers in the family include Domenico’s cousin’s kids, Constantino (fl c1550-1600) who worked in Nuremburg and published a book of canzonettas, and Matthia (1550-1616) who was Kapellameiser in Graz and composed canzonettas and villanellas.

Alfonso spent part of his early life in Rome with his notorious father, surrounded by music and musicians. As a young adult, he also spent some time in Lorraine (France) as a court musician for Charles of Guise (1524-1574).

Alfonso went to England for the first time in 1562, probably with his uncle, and found employment in Elizabeth I’s court. There he stayed for the next 16 years. But a dark cloud seemed to follow him everywhere. He made frequent trips to Italy, but neither the pope nor the Inquisition approved of his time in England, which was actively at war with Roman Catholic countries. While in England, Alfonso lost his Italian inheritance, and later, when he returned to Italy, he was charged with crimes in England (in absentia), including robbing and killing another foreigner. He returned to clear his name successfully, but left England in 1578 and never returned.

While in England, Alfonso the Elder had a family. There’s no record of a marriage, so it’s possible that his children were illegitimate. One of these kids, Alfonso the Younger, was born in 1578 and lived in England until his death in 1628. He was a lutenist, viol player, and singer, and was employed at court from 1592. He (the Younger) became teacher to Princes Henry and Charles (later Charles I), and was granted a pension and annuity by James I in 1605. Under Charles I, Alfonso the Younger also became Composer of Music to the King. From 1605 until 1611, he worked on the music for seven masques, along with playwright Ben Jonson (c1572-1637) and architect Inigo Jones (1573-1652).

Some of Alfonso the Younger’s works were published in a book of Ayres (1609) along with more conventional lute songs. His vocal music was similar to his father’s music in both somberness and style. His fantasias and In Nomines (for more on this genre of music, see my blog on John Taverner) are distinctive among his instrumental music, which also includes dances for viols and pieces for lute. Alfonso the Younger had three sons who were also musicians, another Alfonso (c1610-1660), a viol and wind player who took over his father’s appointments; Henry (c1615-1658), a singer, wind player, and composer, who was a musician until 1645 and then went off on a military expedition to Jamaica, where he was killed in 1658; and John (1626-1682), who was an organist and composer at Ely Cathedral from 1662 and whose works include several services, anthems, and harpsichord dances.

At any rate, after founding a musical dynasty, Alfonso the Elder left for Rome in 1580. Elizabeth I tried to get him to come back to England so fervently that some sources suggest he was her spy, and that she was so anxious for his return because she needed information (after all, she had William Byrd and Thomas Tallis to write music for her). There isn’t much more than circumstantial evidence of this, though, and he refused to return to England.

Alfonso the Elder wrote “madrigalian” motets and simple Latin hymn settings in a style similar to those of William Byrd. This was a style that had appeared in England in the 1580s when the English mania for all things Italian reached its height. Examples of this mania can also be found in the poetry of Edmund Spenser (c1552-1599) and Philip Sidney (1554-1586).

Italian manuscript collections had reached England with Alfonso the Elder in 1562, but it took a while for tastes to turn to the new style. And although he’s only given tiny little biographies in the music history texts, his music was included in anthologies by the British, Italians, and Frenchmen. Not many can say that. And madrigals soon became the most prevalent type of composition in England. He has to get credit for bringing the madrigal to England.

Alfonso the Elder’s style was more conservative than famed Italian madrigalists Luca Marenzio (c1553-1599) or Luzzasco Luzzaschi (c1545-1607), but it suited the more uptight English tastes. Most of his madrigals were for five or six voices, were light in style, and they ignored the Italian musical developments, such as chromaticism and word painting. They were described by Thomas Morley (c1557-1602) as technically skillful when he published several of Ferrabosco’s works in 1598 (10 years after Ferrabosco’s death).

Alfonso also wrote sacred music, including motets, lamentations, and several anthems, all a capella (without instrumental accompaniment). He also wrote instrumental music, including fantasias, pavans, galliards, In Nomines, and passamezzos for a variety of instrumental combinations, including lute and viols.

While in England, he worked hard to interest English musicians in Italian music, and although his style was conservative, he is the composer most generously represented in Musica Transalpina, a compilation of Italian madrigals translated into English and collected by Nicolas Yonge and published in 1588 by Michael East (c1580-1648).

In total, Ferrabosco wrote more than 60 sacred works, mostly motets and lamentations for five and six voices. Technically, he was most influenced by Orlando de Lassus (c1532-1594, biography to come). In turn, he inspired William Byrd (1543-1623, biography to come) and other English composers. Most of the texts he chose are sad and his melodic lines reflect his preoccupation with plaintive and meditative subjects and emotions. Perhaps he homesick for Italy.

In the larger sense of music history, his work wasn’t as important as that of other Italian madrigalists, although he influenced them with what he’d learned from the English. It certainly also worked the other way, as he was the only Italian madrigalist in England at the time, and without his efforts, Byrd would have had no teacher in the style.

He published two books of five-part secular madrigals in 1587 and wrote 70 more in five or six voices. His style is simple compared to others of his time—he was admired for skill rather than for innovation.

Ferrabosco wrote a few chansons, Latin songs, fantasias, and dances for the lute, and some fantasias and In Nomines for viols.

In the last years of his life, Alfonso was court musician to the Duke of Savoy in Turin. He died in Bologna at the young age of 45.

Sources:

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1994.

“The Concise Oxford History of Music,” by Gerald Abraham. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1979.

“A Dictionary of Early Music; from the Troubadours to Monteverdi,” by Jerome & Elizabeth Roche. Oxford University Press, New York, 1981.

“Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music,” by Don Michael Randel. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978.

“The New Grove High Renaissance Masters,” by Gustave Reese, Jeremy Noble, Lewis Lockwood, Jessie Ann Owens, James Haar, Joseph Kerman, Robert Stevenson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1984.

Composer Biography: John Sheppard (c1515-c1560)

John Sheppard (also Shepherd) is one of the less famous composers from Henry VIII’s court. He gets called a “turbulent and eccentric figure, too little of whose music has been printed” by the textbooks, but sadly, they don’t say what was so turbulent or eccentric about him. And despite his anonymity today, he was one of the major composers of the Pre-Reformation period between 1530 and 1560.

The only clue I have to his irascibility is a story about Sheppard’s recruiting practices. Apparently, it wasn’t uncommon for really good choirboys to be kidnapped occasionally, and there’s a story that Sheppard kidnapped a boy who was tied up and dragged all the way from Malmesbury to Oxford, about 60 miles. It seems like the boy would have died after such an experience, so it’s probably an exaggeration.

Sheppard was Informator Choristorum at Magdalen College, Oxford, between 1543 and 1548, which means that rather than being the conductor of the choir, he was the teacher or Master. His work there brought him to the attention of the King, and he became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal by 1552. Sources show that there were gaps in his membership both at Magdalen College and at the Chapel Royal, but they don’t explain the gaps, although one consideration is that his tenure at court almost lines up with Queen Mary’s reign.

Sheppard’s musical techniques were often conservative (and considered old fashioned in his lifetime) but his music is really quite rich. The vocal textures are fairly uniform, without much coloration by imitation or repetition, but he combines virtuoso scoring (reminiscent of the Eton Choirbook period—see my post On Henry VIII’s MP3 Player for more about the Eton Choirbook) with chordal constructions and masterly control of the play between harmony and rhythm.

He wrote large number of hymns and Office responds, and through them, we can see the changes of taste in music for the Office, from the ornate Latin works when England was still Catholic, the ornamental form during Mary’s reign, and simple syllabic themes from Edward VI and Elizabeth I’s reigns.

Most of Sheppard’s surviving music for the Latin rite was probably written during Mary’s reign. His six-voice Magnificat has florid counterpoint and no imitation, and belongs to the tradition of the Eton Choirbook composers. Among his more modern works are a four-voice Magnificat, the Missa Cantate, and the Mass “The Western Wynde.” His best work included vigorous counterpoint around a plainchant (busy voices around a simple melody).

Sheppard shows foreign influence in his Frences Mass in the Eton Choirbook. His output was second only to that of William Byrd (biography to come) among 16th century composers. He wrote five Masses, 21 Office responds, 18 hymns, and a quantity of votive antiphons, psalms, canticles, etc.

HIs English-language works, which include 15 anthems and service music, date from Edward’s reign. During Mary’s reign, there was an outpouring of Latin psalm-settings by Tallis, Tye, Sheppard, and Robert White (c1530-1574).

He worked with Thomas Byrd (William’s father, whose dates are uncertain and about whom very little is known) on a collaborated psalm setting with Thomas Mundy (dates unknown), called Similes illis fiant.

Reports on his activities are few. All we know, really, is that in 1554, he applied for the Doctor of Music degree from Oxford, and that he was last listed in Chapel Royal documents in 1559. He might have died, or he might simply have retired. One source lists his death in 1559, several list it in 1560, and one lists it as 1563 and mentions London as the location.

Sources:

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanly Sadie. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1994.

The Pelican History of Music, Book 2: Renaissance and Baroque,” edited b Alec Robertson and Denis Stevens. Penguin Books, Harmondshire, 1973.

“The Concise Oxford History of Music,” by Gerald Abraham. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1985.

“Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music,” by Don Michael Randel. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978.

Composer Biography: John Merbecke (c1505-c1585)

In 1543, composer John Merbecke was condemned to death for having Catholic sympathies in Protestant England under Henry VIII. He was pardoned in the following year, and lived on to write The Booke of Common Praier Noted (in 1550), which set the new English liturgy into syllabic chant (one note per syllable). It was based on the old Sarum chants, from the 11th century Salisbury Cathedral’s Roman rites, and although his book was rendered obsolete in 1552 by a new prayer book (The Second Book of Common Prayer), it returned to use sometime around 1850.

When the Second Book came out in 1552, Merbecke joined the pro-Calvinists and other Reformers and condemned all music as vanity. Imagine! Giving up your life’s work—John Taverner had done the same thing in 1530, so it wasn’t unprecedented.

Merbecke’s family life and background are not very well-documented. The date of his birth is vague—it was sometime between 1505 and 1510, and it’s thought that he was born in Windsor or Beverly in Yorkshire.

In 1531, he became a lay clerk (which means that he didn’t become a monk or a priest—musicians were often priests or monks because that was the best way to get an education if you weren’t of noble birth) at St. George’s Chapel in Windsor, and later, he became the organist there. In 1543, he and four others were convicted of heresy and sentenced to be burned at the stake. Stephen Gardiner (c1493-1555), Bishop of Winchester, intervened and he received a pardon. In 1544, after his release from prison, he returned to St. George’s and devoted his life to the study of Protestantism. (In other words, the charges against him weren’t false.)

An English Concordance of the Bible, which Merbecke had been preparing at the suggestion of Richard Turner (d.c1565), who was a staunch supporter of royal supremacy, was confiscated and destroyed as a result of his conviction and imprisonment. A later version of this work, the first of its kind in English, was published in 1550 with a dedication to Edward VI, who was king by then.

Although he composed Latin music for the Catholic church in his younger years, he’s best known for The Booke of Common Prayier Notes (1550), which was the first musical setting of the services described in the 1549 Prayer Book. His book was probably designed for use in parish churches rather than cathedrals and consists of simple monadic (no harmonies) music in the style of plainchant, written in block note neumes (see my post on the History of Music Notation for more on this), in the newly popular one-note-per-syllable style.

He died, probably while still organist at Windsor, about 1585. His son, Roger Merbecke (1536-1605), became a noted classical scholar and physician.

In the first half of the 19th century, political and religious reformer John Jebb (1736-1786) inspired a renewed interest in liturgical music within the Church of England. Jebb drew attention to Merbecke’s Prayer Book settings in 1841. In 1843, plainsong music for all the Anglican services was publicized, including nearly all of Merbecke’s settings, which had been adapted for the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer, then in use.

During the latter half of the 19th century, there were many different editions of the Merbecke settings, particularly for the Communion Service. These settings were widely used until the 1662 Book of Common Prayer was supplanted by more modern liturgy in the late 20th century.

Other denominations than Church of England have used Merbecke’s settings, including the Roman Catholic Church, who used it for the new English language rite following the Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965 (Nicene Creed).

An amateur choir for mixed voices at Southwark Cathedral in London is named the Merbecke Choir in his honor, because Merbecke’s heresy trial was partly held at the church in 1543. Merbecke’s complete Latin music was recorded by The Cardinals’ Musick, under the direction of Andrew Carwood in 1996.

Sources:

The Pelican History of Music, Book 2: Renaissance and Baroque,” edited by Alec Robertson and Denis Stevens. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1973.

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1994.

Composer Biography: Christopher Tye (c1500-c1572)

Christopher Tye had part, along with John Taverner (1495-1545) and Thomas Tallis (c1505-1585), in shaping English music in a way that made it possible for more famous composers, such as William Byrd (1543-1623) and Henry Purcell (1659-1695) to be as remarkable as they were. You’ve probably heard of those last two. This is the story of an unsung hero—or at least seldom sung.

Tye was born at Doddington-cum-Marche on the Isle of Ely sometime between 1500 and 1505. Not much is known about his family, but we do know some of his whereabouts. He was at King’s College, Cambridge, between 1508 and 1545. Considering his extreme youth when he arrived, he was probably a choirboy there. He also earned a Bachelor’s degree at King’s College in 1536 and became a lay clerk in 1537.

Tye officially began his adult musical career sometime after 1525 as an organist. By 1543, he was choirmaster at Ely cathedral and later became organist there in 1559.

Next, he earned a Doctor of Music degree at King’s College in 1545. Because one wasn’t enough, he earned another doctorate at Oxford in 1548.

Tye was introduced at Henry VIII’s court in the late 1540s and he became Prince Edward’s music tutor. It’s possible that he was also Mary and Elizabeth’s tutor. There were a lot of heavy hitters at court already, including William Byrd, Thomas Tallis, John Merbecke, and John Sheppard. Tye stayed at Ely through the reign of Queen Mary (from 1553 until 1558) despite his apparent Protestant leanings. Mary probably had some affection for him if he had been her tutor.

The title page of Tye’s Actes of the Apostles (London 1553) describes him as one of the Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal, but it isn’t known when he joined that band of auspicious musicians. (For more on the Chapel Royal, see my blog On Henry VIII’s MP3 Player.)

He was well-respected among his peers and among the royals. King Edward VI reportedly quoted his father, Henry VIII, as saying that “England hath one God, one truth, one doctor hath for music’s art, and that is Doctor Tye, admired for skill in music’s harmony.”

Two or three years after Elizabeth became queen, Tye’s Protestant piety led him to become a rector, although people said that he was a terrible preacher. Unlike John Taverner, who renounced music as part of his Calvinist leanings, Tye thought that music helped reinforce the message of the scripture to the listener. He is given at least partial credit for inventing the musical form known as the anthem. (For more about anthems, you’ll want to read my blog on William Byrd, coming soon.)

Matching his actions to his ideals, Tye set the first 14 chapters of the New Testament book “Acts of the Apostles” to music. Although the music he wrote was good, he was a terrible librettist. In fact, even Tye said that his text was “full base.” Nevertheless, he meant for the piece to be sung accompanied by a lute, and said that if people couldn’t sing it themselves, they could enjoy listening to the music and learn from it. He never finished the whole Bible book, but he saw music as an excellent method for interacting with scripture.

In the 1520s, Thomas Cranmer (1489-1527) wrote a letter to Henry VIII (1491-1547) in which he said that a “song should not be full of notes, but, as near as may be, a syllable for every note,” and saying that the new English music should take this form. Taverner was so disgusted that he gave up composition altogether. But Thomas Tallis (c1505-1585) and Tye continued to write music for the new Protestant services, although these works were not as technically interesting or artistic as the Latin music had been. Both composers continued writing secular Latin motets, but no more Masses.

Only 11 of Tye’s surviving works are complete. There are three Masses, about 18 Latin motets, 15 English anthems and other English settings, and around 30 consort works (for families of instruments. (For more on instrument families, see my blog posts Instrument Biography: The Vielle, Instrument Biography: The Cornetto, and Instrument Biography: The Recorder.)

Of his consort works, there were more than 20 individual five-voice In Nomine. (My post Composer Biography: John Taverner covers the tasty morsel called In Nomines.)

His antiphon Ave caput Christi dates from c1530-1535. He wrote a five-voice Mass (published in the Peterhouse Partbooks—a collection of music manuscripts in a set of 17 books from the 1540s and earlier) and a Mass called “Western Wynde” that may both date from before 1540.

Tye’s Latin church music (Masses, antiphons, Magnificats, etc.) were probably written during Henry VIII’s reign and shows the influence of Robert Fayrfax (1461-1521) and his contemporaries. The 15 surviving English anthems probably date from Edward VI’s reign (1547-1553). Tye’s Latin Psalm settings Omnes gentes, plaudit and Cantate Domno, and his six-voice Mass Euge bone, all deftly use the Continental motet techniques and probably date from Mary Tudor’s reign (1553-1558).

Tye’s Latin music also includes psalm settings and Masses, notably one set on The Western Wynde, a folk song of the time, and also set by John Taverner and John Sheppard. He composed works in English for the Church of England, including services and anthems, and his hymn tune “Winchester Old” is probably based on a piece from his own Acts of the Apostles.

Tye occasionally used the Continental style of repetition to the point of his music sounding a bit routine. But the Actes of the Apostles (1553), which was meant for instruction and recreational use, features metrical texts and simple four-voice music that’s rather nice. He dedicated it to King Edward VI.

Tye also used imitation (A Continental style where each voice repeats a certain musical gesture, sometimes in a different place in the scale, and sometimes identically) more consistently than Tallis in his anthems. But it wasn’t until William Byrd that the first great music for Anglican worship was produced. Tallis and Tye were models for Byrd.

Tye died in 1572 or 1573, apparently still musically active under Elizabeth I. Anthony Wood (a 17th century antiquary) relates that Tye was a peevish and moody fellow, especially as he aged. Tye played the organ in Elizabeth’s chapel, but it didn’t always please her. She occasionally sent the verger to tell him that he played out of tune. He responded that her ears were out of tune.

Sources:

“The Pelican History of Music, Book 2: Renaissance and Baroque,” edited by Alec Robertson and Denis Stevens. Penguin books, Harmondsworth, 1973.

“The New Grove High Renaissance Masters,” by Jeremy Noble, Gustave Reese, Lewis Lockwood, James Haar, Jessie Ann Owens, Joseph Kerman, Robert Stevenson. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1984.

“The Concise Oxford History of Music,” by Gerald Abraham. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1985.

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1994.

Composer Biography: John Lloyd (also Floyd or Flude) (c1475-1523)

Not much is known about John Lloyd, but he was part of the important Chapel Royal, court musicians to English royalty, in the 16th century, and his name comes up frequently when researching other composers during Henry VIII’s reign.

Lloyd was either English or Welsh, and he was a priest. He served the parish of Munslow in Shropshire from 1508, and not long afterward, in 1510 or so, he became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal and went to court.

He wrote at least one Mass. It was highly florid and melismatic with soaring melodic lines and euphonious counterpoint, much like music on the Continent had been before Henry VII’s time and how it became again after Henry VIII and the Reformation. The chant (O quam suavis) on which his Mass is based is very long.

Henry VIII made efforts to end English musical isolationism, and in addition to arranging marriages and other diplomatic efforts, he took members of his Chapel Royal to Europe and encouraged his musicians to exchange knowledge. Lloyd probably went with Henry VIII to meet the Burgundian Chapel of Margaret of Austria with the rest of the Chapel Royal in 1513, and in 1520, to the Field of the Cloth of Gold, where they met the French Chapel of Francis I. While they were there, it was Trinity Sunday and they sang the movements of a Mass alternately, first the French Chapel Royal and then the English Chapel Royal and so on. When they all returned to England, Lloyd left the group and went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

Just as we don’t know much about his life, we also don’t know much about his compositions. He wrote two puzzle canons (where much of the melody and how to sing the piece must be worked out by the performers) that are preserved in King Henry VIII’s Manuscript (see my post On Henry VIII’s MP3 Player for more on that), and in them, we hear the last remaining relics of medievalism.

His Mass that I mentioned earlier, O Quam suavis, has a tenor line that provides the solution to the puzzle of a Latin canon.

Sources:

“The Concise Oxford History of Music,” by Gerald Abraham. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1985.

“The Norton/Grove Concise Encyclopedia of Music,” edited by Stanley Sadie. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1994.

“A Dictionary of Early Music from the Troubadours to Monteverdi,” by Jerome and Elizabeth Roche. Oxford University Press, New York, 1982.